| Bamboo Bamboo (Arundinaria

alpina), restricted in the wild to the

high altitude south-east of Bwindi

Impenetrable National Park, is a very

important resource for home and granary

construction in the Katojo, Mushanje and

Nyamabale parishes. Young bamboo culms

also provide a valuable material for

basketry, for commercial sale and home

use. Bamboo for this purpose is obtained

from Echuya Forest Reserve, and probably

also from Bwindi. In contrast to Mount

Elgon, bamboo shoots are not eaten by

people in this area.

Although theoretically not permitted

when this study was carried out,

harvesting of bamboo still took place

within Bwindi Impenetrable National Park.

Quantitative resource surveys indicate a

low level of cutting in the past. Work

with resource users also showed that a

high proportion of bamboo culms (stems)

were unacceptable for building purposes

due to the high incidence of borer attack

(moth larvae). Although it is a key

resource for people and wildlife, few

data are available for Uganda on the

biology and biomass production of A.

alpina, and research work is recommended.

It is also suggested that an adaptive

management approach is taken to bamboo

harvesting in multiple-use zones covering

the bamboo thicket. This could be

undertaken seasonally by licensed bamboo

harvesters from the Katojo, Mushanje and

possibly Nyamabale parishes, and

permitted on a trial basis. Development

of edible bamboo shoot harvesting for

local or external markets is not

recommended.

Bamboo is a widely used forest product

of great importance to rural communities

in many tropical forest areas,

particularly in Asia, but also in East

and Central Africa. Arundinaria alpina

thickets are found in Afromontane forest

in East Africa from 2400-3000 m,

occurring to 3200 m on Mount Kenya and as

low as 1630 m in the Uluguru mountains

(White, 1983).

In Uganda, bamboo is cut in the

Rwenzori, Mount Elgon, Mgahinga, Echuya

and Bwindi Impenetrable forests (Howard,

1991). It is also cultivated on a small

scale in the DTC area. Bamboo thicket

occurs in a limited 0.4 km˛ high

altitude area in the south-east of Bwindi

Impenetrable National Park (Butynski,

1984). Forty-one percent (48) of

respondents surveyed in the DTC area used

bamboo, probably from cultivated sources

(Arundinaria alpina and the exotic bamboo

Bambusa sp.) (Table 7) as well as from

the wild (Kanongo, 1990).

From field observation in the parishes

adjacent to the south-eastern corner of

Bwindi Impenetrable Forest it is clear

that home construction (cross-pieces) is

a major use of bamboo, followed by use

for granaries and baskets (Table 7).

| Table

7. Extent of use, users and

source of bamboo in the DTC area

(data from Kanongo, 1990). |

| No.

users (n = 116) |

Use

(n = 52) |

Bamboo

source (n = 54) |

Yes 48

(41%)

No 68 (59%) |

Other

(fences, firewood and

home construction): 40

(77%) Granaries:

7 (13%)

Baskets: 5 (10%)

|

From

forest (freely taken):26

(48%) From forest

(bought through Forest

Department): 24

(44%)

Grown at home: 4 ( 7%)

|

|

Bamboo was one of the

most important "minor forest

products" sold by the Forest

Department, with almost 500,000 bamboos

sold annually from former Central and

Local Forest Reserves between 1961 and

1962 and between 1963 and 1964 (1961-62:

515,000 bamboos; 1962-63: 450,000

bamboos; 1963-64: 459,882 bamboos)

(Forest Department, 1964).

| |

|

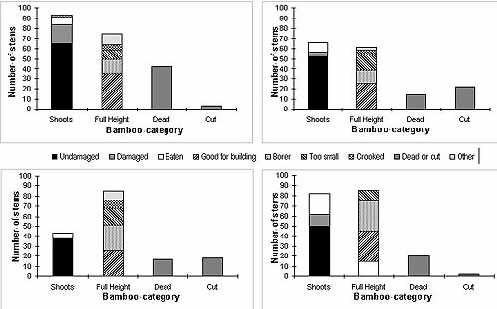

| Figure 3. Data

from four plots in the bamboo

zone, assessing shoot density and

damage, and the value of bamboo

stems within 10 x 10 m plots for

building purposes. Note the high

proportion of stems that are

unsuitable for building purposes

(due to borer damage, crooked

shape, small size or other

factors), the proportion of young

shoots eaten by primates and the

low level of bamboo cutting. |

Although not mentioned

in the former forestry working plan for

Bwindi Forest (Leggatt and Osmaston,

1961), plans were drawn up for regulated

cutting in Mgahinga Forest, where an

average of 77,400 bamboos were cut

annually from 1955 until 1966-67 from

within four coupes, one harvested per

year (Kingston, 1967). The previous

extent of use in Bwindi Impenetrable

Forest is unknown, although a survey by

Kanongo (1990) indicates that out of 54

respondents, 92% (50) obtained bamboo

from Bwindi Forest, with or without

licensing (Table 7).

| Box

4. Recommendations for basketry

species * Quality

of granary construction varies

considerably, from excellently

made granaries enabling effective

protection of crops to flimsy

granaries that do not. Skilled

granary weavers are well known

within each community, and it is

suggested that these skilled

local people are involved in

teaching improved granary design

to DTC farmer groups, for example

by using Pennisetum purpureum

(elephant-grass).

* Research into major causes

of stored crop losses and

appropriate solutions to this

problem needs to be undertaken,

possibly by Mbarara University of

Science and Technology (MUST).

* Form basket-making societies

in each parish and meet with the

existing stretcher-bearer

societies to discuss resource use

issues covered here. Licenses

enabling members to collect

forest plants from multiple-use

areas would be on a similar

format to those issued to

beekeepers.

* CARE-DTC could facilitate

the commercial marketing of

finely made baskets (e.g.

finger-millet baskets) to improve

local income and keep traditional

skills alive, either through

export or sale to tourists at

camps being established with the

development of the Tourism plan

for Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

National Park. The quality of

these baskets can compete with

basketry worldwide. Materials for

commercially produced baskets are

discussed below.

* Unrestricted use of Eleusine

indica (enchenzi), Plantago

palmata (embatambata), Cyperus

papyrus (efundjo) and C.

latifolius is suggested. These

are the most commonly used

species apart from bamboo, and

are the materials which could be

used for finely made,

export-quality basketry.

* Unrestricted local use of

Raphia farinifera leaves for

basketry.

* It is recommended that

Smilax anceps (enshuli),

Marantochloa leucantha (omwiru)

and Ataenidia conferta

(ebitatara) are harvested

seasonally by two

"specialist harvesters"

selected by the parish society.

For Smilax, this would relate to

most parishes, but for

Marantochloa and Ataenidia, this

would only apply in lower-lying

parishes (e.g. Mukono, Karangara

and Rubimbwa). An open season

would be during the peak

basket-making time of the year

(at a less busy point in the

agricultural cycle, probably

May-August).

*Discussions should be held

involving management staff from

Bwindi Impenetrable National

Park, Uganda Tea Growers

Corporation (UTGC) and DTC

regarding the management of

Loeseneriella apocynoides

(omujega). This is a problem of

common concern to all

organizations, as availability of

this species affects tea-picking,

income to local out-growers and

forest. At present, UTGC may be

unaware of the over-exploitation

of this forest climber. They also

appear mistakenly to regard this

tea-basket weaving material as a

"free good", whereas

UTGC supply yellow "picking

jackets" and gum-boots to

their out-growers. L. apocynoides

(omujega) is a relatively scarce

species which is important for

many other purposes in the

surrounding community,

particularly for stretchers

(engozi), and not only to

tea-growers. Sustained management

of this species is needed, and

this should involve the

tea-growers and UTGC. For

example, the UTGC may have

nursery facilities and staff for

tea plantations who could also

assist in experimental

cultivation of L. apocynoides

(omujega), and probably more

effectively, collection of seed

and cultivation of Phoenix

reclinata (enchindu, wild date

palm), which is already used as a

substitute for L. apocynoides in

weaving tea-baskets in the

Ishasha area. The palm leaf-stems

can be cut without damage to the

plant. Phoenix reclinata is

faster growing, occurs along

alluvial plains of the Ishasha

river and is a common palm in

swamp forest or on termite mounds

in seasonally flooded grassland

in Uganda. The UTGC staff may

also be able to assist with

cultivation of other species (see

below).

* Subject to more detailed

field research, a closed period

of at least four years should be

considered for Loeseneriella

apocynoides (omujega), after

which the stretcher-bearer

society (ekyibinachengozi) groups

should have precedence in

controlled harvesting of this

species. There are very few

stretcher-makers in the DTC area,

and they collect their L.

apo-cynoides (omujega) in forest

as close to their homes as

possible. It is unlikely that

they would be prepared to travel

long distances in difficult

terrain to fit in with a

rotational system, yet a single

multiple-use area for a parish is

unlikely to have enough material

for sustained use of this

species, and rotational

harvesting is a useful

alternative to either

over-exploitation or a complete

ban on use of this species. It is

suggested that the following

approach be implemented on a

trial basis: (i) through the

stretcher bearer societies,

determine the number and

distribution of stretcher makers;

(ii) after discussion about this

problem of common concern,

involve the stretcher-bearer

society members from the 18

parishes immediately adjacent to

the forest in collection of

material on a rotational (20-year

rotation) basis by selected

society members, for supply to

the society's stretcher-makers;

(iii) through these L.

apocynoides gatherers, and if

possible, fixed forest plots

inside and outside multiple-use

areas, monitor the status of this

species.

* DTC, through community

extension agents (CEAs) and

nurseries (e.g. Buhoma and

Kitahurira nursery), should

assess the potential for

cultivation of Marantochloa

leucantha (omwiru) and Ataenidia

conferta (ebitatara). Some

farmers are already cultivating

Cyperus latifolius in the Ishasha

area (May 1992).

|

Management of bamboo thickets for

sustainable use is relatively simple

compared with Afromontane forest, as

bamboo thickets have a lower diversity

and complexity in terms of age/size

classes and uses. Bamboo is an important

resource which is fast-growing and

relatively resilient to harvesting, with

new culms produced from underground

rhizomes. Current levels of harvesting

are relatively low, even in favoured

sites (Figure 3, page 30).

It is suggested that harvesting be

considered within multiple-use zones,

with potential harvesters and

DTC/national parks staff involved in

resource surveys and setting quotas as an

"action research" project. The

following factors need to be taken into

account, however, in considering this

proposal.

- Harvesting within the bamboo

thicket in Bwindi Impenetrable

Forest is not uniformly spread,

but is largely restricted to

three parts of the bamboo zone

(Mpuro, Omushenje and Kasule).

This is a result of the difficult

access from surrounding parishes,

the problems of transporting long

(often >5 m) bundles of cut

bamboo through forest in steep

terrain, and possibly also due to

fear of elephants. Setting of

quotas and a rotational

management system should

therefore not be based on the

entire area of bamboo, or even

that within multiple-use zones,

but on a far smaller area with a

consequently smaller carrying

capacity.

- Although above-ground biomass of

Arundinaria alpina is high (100

tons per ha (Wimbush, 1945) and

growth rates are fast compared to

forest trees, with culms reaching

full height in 2-4 months with

stems senescing after 7-14 years

(Were, 1988), this study

indicates that a much lower

proportion of stems (or biomass)

are suitable for harvesting for

the following reasons, lowering

the carrying capacity of bamboo

stands:* although mature culms

dominate bamboo thicket, the

majority of these would be

rejected by harvesters due to a

high incidence of moth larval

borer attack (Figure 3);* a

percentage of culms are crooked,

broken or too young.

- Young shoots, which are produced

annually during the rainy season

(Were, 1988), break off easily,

and would be affected by

harvesting activity. Young shoots

are also eaten by animals (mainly

primates), with an average of

15.5% of shoots eaten out of four

sample plots.

- Cutting intensities reportedly

affect regrowth rates. With

clear-cutting, it took 8-9 years

to obtain full-sized culms; if

10% of old culms were left

standing and evenly distributed,

full-sized new culms could be

produced after 7-8 years, and if

50% of culms are left standing,

the recovery period may be

reduced to 3-4 years (Wimbush,

1945). Although these plots were

placed near to the road, the

level of harvesting was low. This

could be attributed to

"closure of the national

park to bamboo cutting", but

a similarly low level of bamboo

cutting was also observed along

the main path to the densely

populated parish adjacent to the

bamboo zone.

- The previous system of selling

licenses as a means of

controlling and monitoring the

harvesting of forest produce

(including bamboo) failed for the

reasons given by Howard (1991),

where declining purchasing power

of forestry salaries led to lack

of commitment of staff to their

work and unofficial sale of

bamboo or cutting licenses to

earn supplementary income. It

would be important to avoid this

problem in the future if

sustained harvesting of bamboo is

to be implemented in Bwindi

Impenetrable National Park. In

Mghahinga forest, it was noted

that although bamboo harvesting

was prohibited within the SNR

(strict nature reserve) section

of Mgahinga, there were extensive

signs of illegal bamboo cutting,

and recommended that harvesting

pressure be shifted to more

abundant and better quality

stands of bamboo in Echuya Forest

Reserve. The extent of managed

use of bamboo through licensed

harvesting in Echuya Forest is

uncertain, however (K. Sucker,

pers. comm., 1992).

| Box

5. Recommendations for bamboo

* Detailed mapping of the

bamboo thicket in Bwindi

Impenetrable Forest is needed.

* Sustainable harvesting

should be carried out on a trial

basis, with resource users

involved in the decision-making

process regarding resource

assessments and management.

Harvesting blocks/coupes need to

be established in the Mpuro,

Mushenje and Kasule areas, and

resource assessments carried out

with resource users (bamboo

cutters) selected through the RCs

of the Katojo, Mushanje and

possibly Nyamabale parishes.

Quotas should be set on the basis

of resource assessments.

* Two cutting seasons should

be considered (possibly

July-August and January-March).

* A limited number of

specialist harvesters should be

licensed to harvest for people in

the parish who require bamboo.

Licenses should be similar to

those issued to beekeepers, and

should not be sold or be

transferable. Separate licenses

need to be issued to

basketmakers.

* Cultivation of bamboo should

be an important component of the

DTC agro-forestry programme.

* Research is needed on

biomass production and effects of

harvesting on Arundinaria alpina.

Most recommendations and

information on these issues

(Kingston, 1967; Kigomo, 1988;

this study) are based on the

results of a short-term study

published 50 years ago (Wimbush,

1945).

* Additional research on the

population biology and gap

dynamics of Arundinaria alpina is

important for resource use and

maintenance of this vegetation

type as management objectives for

Bwindi Impenetrable National

Park. White (1983), for example,

suggests that trees scattered in

bamboo stands become established

in the 30-40 year intervals of

bamboo flowering and die-off.

According to Glover and Trump

(1970), Arundinaria stands are

fire-induced in what was formerly

Juniperus forest on the Mau

Range, Kenya. Whether this is the

case in Bwindi Impenetrable

Forest or not, or whether

establishment of bamboo within

forest, or trees within bamboo is

due to other factors (e.g.

elephant and "canopy

gaps" formed in bamboo due

to the combined effects of wind

and borer attack weakening mature

culms, both of which have been

observed in this study) is

uncertain, and needs to be

investigated.

|

| |

|