| Major forest

products:wood Blacksmiths and Bellows

Blacksmiths are a small but important

group of specialists who play a valuable

role in the farming community of the DTC

area, producing agricultural implements

and tools (photo 3, page 9). Smelting of

haematite is no longer carried out, but

scrap metal is re-worked into tools and

hardware (e.g. hammers, locks, dog

bells).

The secondary forest tree species

Polyscias fulva (omungo) (photo 4, page

9) is the major source of wood for

construction of bellows, whilst exotic

species such as black wattle (Acacia

mearnsii) have been favoured for charcoal

use since at least the 1960s.

It is recommended that blacksmiths are

allowed to continue to harvest Polyscias

trees for construction of bellows. The

role that blacksmiths can play in rural

development and possibly sensitively

planned specialist tourism needs to be

recognized. If not, this traditional

skill and technology will disappear.

Wood is used by blacksmiths (omuhesi)

for two main purposes. First, in

construction of bellows (omuzuba), where

large trees with low density

("soft") wood are selected, and

second, for charcoal, where high density

woods are preferred.

The use of bellows for iron-working

represents an historical link with the

technology introduced to this region some

2000 years ago. Both the technology and

the traditional knowledge this represents

is disappearing, however, due to

competition from industrially produced

goods. In 1968, only four blacksmiths

interviewed in Kigezi by White (1969)

claimed to smelt iron-ore. Although

favoured sites for collection of

haematite and smelting technology are

still known, iron-smelting no longer

takes place. Instead, scrap metal from

old cars or from broken agricultural

tools is reworked.

Blacksmith numbers are considered to

have declined, and most blacksmiths are

older men over 50 years. White (1969),

for example, records 23 blacksmiths

working in the Kitumba area in Kigezi.

From enquiries made in this survey, it

would appear that at most only 2-4

blacksmiths work in each parish, and in

some parishes there are none.

Most blacksmiths have one set of

bellows; most (n = 9) of these are made

of Polyscias fulva (omungo) wood, and a

single bellows was made from Musanga

leo-errerae (omutunda). Both are favoured

for their soft wood, which can be

hollowed out to form the drums and pipes

of the bellows. Despite the low density

of Polyscias wood, bellows last 20-30

years, which probably exceeds the time

that it would take P. fulva to reach a

suitable size for bellows construction

(40-50 cm dbh).

Due to their soft wood however, both

Polyscias fulva and Musanga leo-errerae

are avoided for other uses (building,

timber, beer boats). Felling of these

trees for this purpose would be on a

limited scale and restricted to secondary

forest, and it is recommended that

utlization in multiple-use areas be

permitted.

Both exotic and indigenous tree

species were recorded as used by

blacksmiths for charcoal. Black wattle

(Acacia mearnsii) is favoured for this

purpose, a situation unchanged from that

of the late 1960s (White, 1969). Favoured

indigenous species are Syzygium guineense

(omugote) in low-altitude sites, and

Agauria salicifolia (etchigura). Parinari

excelsa (omushamba) and Sapium ellipticum

(omushasha) are also used.

Canoes

Dug-out canoes are made and used at

only one locality in the DTC area (Lake

Bunyonyi, bordering on Nyarurambi

parish). All of these canoes are carved

from cultivated trees, primarily

Eucalyptus (82%), and none is cut in

Bwindi Impenetrable Forest. Canoe

construction is not therefore considered

applicable to forest multiple-use areas

in this study.

Wood

carving - household items

|

| Photo

18.

Carving spoons from

Markhamia lutea (omusavu)

wood. |

|

A range of wooden items is

found in most households in the

DTC area and these are important

in food processing (stamping

mortars and pestles for grain and

groundnuts), collection (milk

pails) and consumption (spoons,

beer mugs) (Photo 18, page

32). Tree use for these

utensils is often selective, with

hardwoods required for mortars,

while softer species are

acceptable for beer mugs and milk

pails. Hardwoods are also

important for walking sticks,

while Rapanea melanophloeos

(omukone) is used for carved

walking sticks for commercial

sale (Table 8, page 33).

|

| |

|

| Table 8.

Plant species recorded

used for wood carving in

the DTC area. |

| Family |

Plant species |

Rukiga name |

Life form |

Use |

| Alangiaceae |

Alangium chinense |

omukofe |

tree |

pestles |

| Apocynaceae |

Pleiocarpa pycnantha |

omutoma |

shrub |

pipe-stems |

| Bignoniaceae |

Markhamia lutea

(**) |

omusavu |

tree |

spoons, mortars |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Drypetes

gerrardii |

omushabarara |

tree |

pestles, sticks |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Drypetes

bipindensis |

omushabarara |

tree |

spear handles, sticks |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Sapium

ellipticum |

omushasha |

tree |

pestles |

| Fabaceae |

Millettia dura |

omutate |

tree |

hoe handles |

| Flacourtiaceae |

Rawsonia

spinidens |

omusalya |

tree |

combs ,walking sticks |

| Moraceae |

Ficus

asperifolia |

omushomora |

shrub |

sandpaper |

| Moraceae |

Ficus

exasperata |

omushomora |

shrub |

sandpaper |

| Myrsinaceae |

Rapanea

melanophloeos |

omukone |

tree |

carved sticks |

| Rosaceae |

Prunus africana |

omumba |

tree |

mortars |

| Rubiaceae |

Rothmannia

longiflora |

oruchiraje |

shrub |

spear handles |

| Rubiaceae |

Aidia micrantha |

orube |

tree |

spear handles |

|

| Note: Species

cultivated are marked

(**). |

|

Although commercial

scale harvesting concentrating on a

single species (e.g. Rapanea

melanophloeos) may result in localized

over-exploitation if not regulated,

impact of use for carving is small

compared to uses such as cutting for bean

stakes or beer boats.

Beer boats (obwato)

Beer boats, the carved wooden troughs

used for brewing banana beer (tonto) are

a very important item to banana farmers

adjacent to the northern sector of Bwindi

Impenetrable National Park. As an

alternative to selling the bananas, they

provide a means of processing and

"adding value" to the crop of

embiri, kisubi, musa or endizi banana

varieties used to make banana beer, which

is then transported to village

markets.

The irony is that in

the process of clearing land for

agriculture, including land for bananas,

most of the large trees (>50 cm dbh)

suitable for making beer-boats have been

destroyed. In addition, stocks of some of

the most favoured tree species used for

beer boats (e.g. Prunus africana and

Newtonia buchananii) have already been

over-exploited by pitsawyers. Although

not perceived as in critically short

supply at present, it can be expected

that in the forseeable future, Bwindi

Forest will be seen as the major

remaining source of beer boats.

|

| Photo

19.

Beer boats provide an

important means of

processing certain banana

varieties in order to add

value and reduce the

weight of banana product

to be transported. This

is done by trampling the

bananas to remove the

juice. |

|

Beer boat production should

not be considered for

multiple-use areas at present.

Emphasis needs to be placed on

encouraging more extensive

planting of Markhamia, Ficus and

Erythrina trees as alternative

sources of beer boats, and

investigating other alternatives

used in tonto producing areas,

for example in Ankole District

and near to Kampala, where

deforestation has already taken

place, but tonto is still

produced in vast quantities.

These alternatives include banana

juice extraction in troughs lined

with cowhide (J. Baranga, pers.

comm., 1992) or cement. Although

bananas are grown throughout the

DTC area, the most important

parishes for banana production,

and tonto making in particular,

are the Nteko, Mukono, Kanungu

and Karangara areas (Photo 19).

With the exception of poor

farmers with very little land who

are unable to produce a banana

surplus for marketing tonto, all

farmers cultivating bananas have

at least one beer boat. At Nteko,

in the sample of 35 farmers

owning beer boats, 63% (22) owned

a single beer boat, 34% (12)

owned two beer boats each, and

the remaining farmer owned three

beer boats. At Nteko, a farmer

with a single beer boat brewed

twice a month, with 175 litres of

tonto produced each time. This

represented an income of 20,000

shillings per beer boat (or

40,000 shillings per month, with

tonto sold for 2500 shillings per

20 litre jerry-can), a very

important aspect of economic

production in the DTC area.

|

Indigenous trees were

used for all the beer boats measured (n =

79) in Nteko and the Ngoto area. Hardwood

trees (Newtonia, Prunus) are favoured for

their durability, and Ficus species, with

less dense or durable wood, because of

their size. Newtonia buchananii and Ficus

sur were the most commonly used for beer

boats in the Nteko area (Table 9), whilst

unidentified Ficus species (probably F.

ovata and possibly F. sur) and Prunus

africana were most commonly used in the

Ngoto area. This results in selective,

localized removal of large Ficus trees

that are a "keystone" species,

being a major food source for frugivorous

birds and primates.

Table 9.

Number of beer boats made

from tree species in the

Nteko and Ngoto areas.

| |

|

|

| |

Nteko (n=46) |

Ngoto (n=32) |

| Newtonia

buchananii |

23 |

|

| Ficus sur (= F.

capensis) (omulehe) |

8 |

|

| Markhamia lutea

(omusavu) |

6 |

1 |

| Ficus spp.

(ekyitoma) |

4 |

14 |

| Prunus africana

(omumba) |

2 |

7 |

| Ocotea usambarensis

(omwiha) |

3 |

|

| Entandrophragma

excelsum (omyovi) |

1 |

|

| Macaranga monandra?

(ekifurafura) |

1 |

|

| Albizia gummifera

(omushebeya) |

1 |

|

| ekiko |

1 |

|

| Sapium ellipticum |

|

3 |

| Erythrina abyssinica |

|

1 |

| Allophyllus sp. |

|

1 |

| ekywezu |

|

1 |

| indet. |

|

1 |

|

Eucalyptus trees were

considered to be unsuitable because they

cracked too easily, although they are

used for making canoes at Lake Bunyonyi.

Beer boats are constructed and then

carried by a group of men to the banana

plantation. Most, 92% (42), beer boats at

Nteko, and 61% (17) at Ngoto were less

than 9 years old, and few beer boats in

either area lasted more than 12 years.

Durability depends on care of beer boats,

which last longer if stacked off the damp

ground on poles or stones, and kept under

a shelter built in the banana field. Many

beer boats, however, are left on the

ground, and merely covered with banana

leaves in between brewing times. Taking

all beer boats measured into account (n =

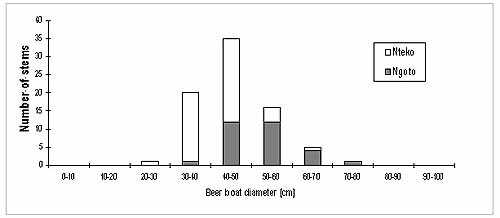

79), 72% (57) were greater than 40 cm

diameter (Figure 4). From these data, and

discussions with local banana farmers, it

was considered that these were made from

trees >50 cm dbh.

| |

|

| Figure

4.

Diameter size class distribution

of beer boats measured on small

banana farms in the Nteko and

Ngoto swamp areas of the DTC

project. |

BUILDING

POLES

Building poles are

required throughout the DTC area.

Selection of poles is based on a need for

straight and preferably durable trees or

tree ferns of a suitable diameter (5-15

cm dbh, Table 10, page 34).

Table 10.

Plant species whose stems

are used for building

poles in the DTC area.

| Family |

Plant species |

Rukiga name |

Life form |

| Apocynaceae |

Tabernaemontana

holstii |

kinyamagozi |

tree (SF) |

| Apocynaceae |

Tabernaemontana

odoratissima |

kinyamagozi |

tree (SF) |

| Apocynaceae |

Tabernaemontana

sp. |

kinyamate |

tree (SF) |

| Clusiaceae |

Harungana

madagascariensis |

omunyananga |

tree (SF) |

| Cyatheaceae |

Cyathea manniana |

omungunza |

tree fern |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Bridelia

micrantha |

omujimbu |

tree (SF, CP) |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Croton

megalocarpus |

omuvune |

tree (SF) |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Drypetes

bipindensis |

omushabarara |

tree |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Drypetes

gerrardii |

omushabarara |

tree |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Drypetes

ugandensis |

omushabarara |

tree |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Macaranga

kilimandscharica |

omurara |

tree |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Sapium

ellipticum |

omushasha |

tree (CP) |

| Fabaceae |

Acacia mearnsii (O

**) |

obulikoti |

tree |

| Fabaceae |

Baphiopsis

parviflora |

omunyashandu |

tree |

| Fabaceae |

Newtonia

buchananii |

omutoyo |

tree (CP) |

| Lauraceae |

Ocotea

usambarensis |

omwiha |

tree (C, CP) |

| Melastomataceae |

Dichaetanthera

corymbosa |

ekinishwe |

tree |

| Myrsinaceae |

Maesa lanceolata |

omuhanga |

shrub |

| Myrtaceae |

Eucalyptus spp. (O

**) |

uketusi |

tree (C) |

| Olacaceae |

Strombosia

scheffleri |

omuhika |

tree (CP) |

| Rubiaceae |

Galiniera

saxifraga |

omulanyoni |

shrub |

| Sapotaceae |

Chrysophyllum

gorungosanum |

omushoyo |

tree (CP) |

| Ulmaceae |

Trema orientalis |

omubengabakwe |

tree |

| |

indet. |

omukarati |

tree |

| |

indet. |

omuzo |

tree |

|

| Note: cultivated

species (**), those

mainly occurring outside

of the forest (O) and

those which coppice

readily (C). Canopy tree

species are marked (CP)

and secondary forest

species (SF). |

|

Favoured indigenous forest species are

Drypetes spp. (omushabarara),

particularly Drypetes ugandensis and D.

gerrardii, Tabernaemontana sp.

(kinyamate), Harungana madagascariensis

(omunyananga) and the tree-fern Cyathea

manniana (omungunza) for durable support

poles and roofing, with Arundinaria

alpina (omuganu) favoured for

cross-pieces.

Compared to cutting of poles from

woodlots (Eucalyptus, Acacia mearnsii or

Sesbania), harvesting from forest is more

labour-intensive due to the comparatively

low density of suitable poles. In a

recent survey conducted in the DTC area

with 120 respondents, Eucalyptus (88%,

106) and Acacia mearnsii (49%, 59) were

the species most preferred for building

and had respectively been planted by 77%

(92) and 36% 43) of respondents (Kanongo,

1990). From field observation, it is

clear that many homes in the DTC area are

built from these cultivated tree species

(particularly Eucalyptus), with the use

of exotic species increasing with

distance away from the forest. It is

recommended that self-sufficiency in

building materials is facilitated through

development of nurseries and supply of

seedlings to interested growers. Opening

of multiple-use areas to allow harvesting

of building poles is not recommended.

Housing is a basic need, and in the

DTC area cultivated and wild plant

resources are an important source of most

low-cost housing material. Although

corrugated iron is favoured and commonly

used, it is difficult to get since the

closure of the Rwanda-Uganda border, and

it is also expensive. Many homes are

therefore thatched with banana fibre, or

if adjacent to wetlands, with Cyperus

latifolius sedge.

Harvesting of thatching materials from

within Bwindi Impenetrable Forest is

negligible, and the two main categories

of building material relevant to

multiple-use areas are building poles and

bamboo. As bamboo is a multiple-use

material occurring in a limited area of

Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, it is

discussed separately (see page 27).

Wood consumption for building purposes

is probably similar to that estimated by

Howard (1991) for the Bwamba region,

western Uganda (0.27 m³ wood per

household per year, or 0.038 m³ per

person per year). Although low compared

to other parts of Africa (e.g. 1.5 m³

per person per year in Owambo, Namibia;

Erkkila and Siiskonen, 1992), population

densities and number of households, and

consequently the demand for building

poles, adjacent to Bwindi Forest are very

high (Figure 2, page 5).

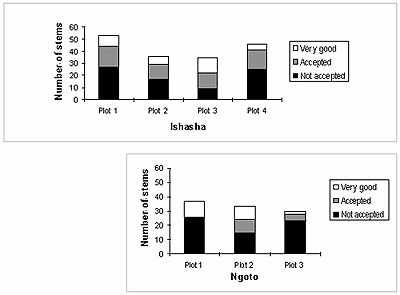

Occurrence of good

quality building poles is patchy,

depending on forest structure and species

composition. Where poles occur, they are

often at a low density (an average

density of 207 very good poles per ha, or

a total of 525 useable poles per ha (n =

7 plots) (Figure 5). This is very low

compared to a stand density of 1363 stems

per ha even in 12 year old (thinned)

commercial stands of Acacia mearnsii with

a 14.4 cm mean dbh (Schönau, 1970) and a

far higher density in local Eucalyptus

plots.

| |

|

| Figure

5. Acceptability

of trees in seven 20 x 20m plots

in Bwindi Forest (Ishasha, n = 4

plots; Ngoto, n = 3 plots)

showing proportion of trees with

stems rated suitable for building

purposes. |

These factors, coupled

to the steep terrain, make cutting of

building poles from the forest a very

time consuming activity, and it is not

surprising that, apart from farmers

living close to the forest, most people

either cultivate or buy building poles of

Eucalyptus, Markhamia or Acacia mearnsii.

Cultivation of building poles is the

major reason for exotic tree planting in

the DTC area (see Table 10) and in Bwamba

(Howard, 1991).

BEAN

STAKES

|

| Photo 20.

Average bean stake

density in fields is

50,000 stakes/ha. |

|

Although over 20

varieties of bean are recognized

in the DTC area, these are

represented by two main growth

forms: climbing beans and bush

beans. Beans are one of the

important staple foods in this

region, and they are cultivated

in all parishes. Major sites for

cultivation of climbing beans are

the Rubuguli, Rushaga, Nteko and

Nyamabale areas. Climbing beans

are more productive, easier to

pick than bush beans and

reportedly softer and easier to

cook, and the DTC project is

promoting the production of

climbing beans for these good

reasons. Bean stakes are

essential for climbing bean

production, and cutting of bean

stakes is an important seasonal

agricultural activity in May and

June. With bean stake density of

c. 50,000 bean stakes per ha

(Photo 20), and lasting only 2-3

seasons, it is clear that huge

quantities of bean stakes are

needed every year.

|

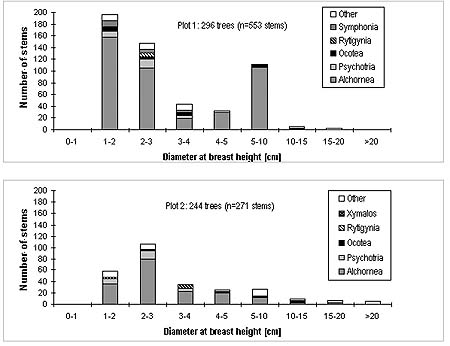

The understorey shrub

Alchornea hirtella (ekizogwa) is one of

the most favoured sources of bean stakes,

re-growing readily and occurring in high

density patches which are focal points

for bean stake harvesting. Despite the

high density of this and other species

suitable for bean stakes in Afromontane

forest (Figure 6), it was nowhere near

the density of bean stakes in fields and

this survey showed that a high proportion

(35-58%) of bean stakes had already been

cut. Although bean stakes must all have

been cut from forest or forest remnants

in the past, many farmers now plant

Eucalyptus or Pennisetum purpureum

(elephant grass) as a source of

stakes.

|

|

| Figure 6. Data

from four forest plots in the

Rushaga area to assess density of

stems used for bean stakes,

showing the patchy distribution

of this resource reflecting

variation due to differences in

topography, species composition

and forest disturbance, from 553

stems in Alchornea (ekizogwa)

dominated understorey (Plot 1) to

189 stems in secondary forest

with an understorey dominated by

Psychotria (Plot 4). |

| |

Demand for bean stakes

is expected to increase, and this cannot

sustainably be met from supplies

available within multiple-use areas. It

is recommended therefore, that in

addition to promoting the cultivation of

climbing beans, the DTC project should

encourage existing initiatives taken by

farmers to cultivate trees and elephant

grass for bean stakes, and facilitate

cultivation of other tree species (e.g.

Sesbania sesban) for this purpose.

Cutting of bean stakes is a

labour-intensive activity. Use of plants

for bean stakes, although favouring

certain species such as Alchornea

hirtella (ekizogwa), is based more on

selection for sites with high densities

of thin (1.5-4 cm diameter), straight

stems in order to maximize stakes cut per

unit time, than on species-specific

selection.

While a wide range of

species (and life forms) is used (Table

11, page 38), favoured sites have a high

density of potential bean stakes: either

disturbed sites (e.g. scrub dominated by

Acanthus arboreus (amatojo) or secondary

forest with understorey, dominated by

Alchornea hirtella (ekizogwa), where

"bean stake density" has been

further increased by coppicing, or

Brillantaisia stands in river valleys.

Similarly, although crop surplus such as

cassava (Manihot utilissima) stems are

used, cultivated stands of Pennisetum

purpureum or Eucalyptus are favoured, as

both give almost consistently straight

stands of bean stakes of a suitable

diameter, and harvesting is quicker and

often closer than indigenous

forest.

Table 11.

Plant species used for

bean stakes in the DTC

area.

| Family |

Plant

species |

Rukiga

name |

Life

form |

| Acanthaceae |

Acanthus arboreus (O) |

amatojo |

shrub |

| Acanthaceae |

Brillantaisia sp. |

echunga |

shrub |

| Asteraceae |

Vernonia sp. |

ekiheriheri |

shrub |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Alchornea hirtella |

ekizogwa |

shrub (C) |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Sapium

ellipticum |

omushasha |

tree |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Manihot utilissima (O

**) |

[cassava] |

shrub |

| Fabaceae |

Tephrosia vogelii (O) |

omukurukuru |

shrub |

| Fabaceae |

Acacia mearnsii (O

**) |

obulikoti |

tree |

| Lauraceae |

Ocotea usambarensis |

omwiha |

tree (C) |

| Myrtaceae |

Eucalyptus spp. (O

**) |

uketusi |

tree (C) |

| Poaceae |

Arundinaria alpina |

omugano |

bamboo |

| Poaceae |

Pennisetum purpureum

(O **) |

|

grass |

| Rubiaceaeo |

Galiniera

saxifraga |

mulanyoni |

shrub |

| Rubiaceae |

Oxyanthus

subpunctatus |

? |

shrub |

| Rubiaceae |

Psychotria

schweinfurthii |

omutegashali |

shrub |

| Rubiaceae |

Rytigynia kigeziensis |

nyakibazi |

shrub (C |

|

Note: cultivated

species (**), those

mainly occurring outside

of the forest (O) and

those which coppice

readily (C). |

|

| Table 12.

Uses and attitudes to

fuelwood use for cooking

in the DTC area (data

from Kanongo, 1990). |

| Main

energy source |

Most

suitable

wood(cooking) |

Woodsource

(cooking) |

Why

scarcity? |

Dry

wood:

120 (100%) Crop

residue:

12 (10%)

Charcoal:

15 (12.5%)

Kerosine:

9 (7.5%)

|

Black

wattle: 87 (72.5%) Eucalyptus:

69 (57.5%)

Others (mainly

indigenous): 21

(17.5%)

Cupressus: 7

(5.8%)

|

From own

land:

102 (85%) Woodlots:

30 (25%)

Forest:

9 (7.5%)

Bought (market):

5 (4.2%)

Charcoal used:

5 (4.2%)

Other sources:

3 (2.5%)

|

Little

tree-planting:

87 (72.5%) Over-population:

48 (40%)

Restricted from

forest:

21 (17.5%)

Climate change:

14 (11.7%)

Other(land shortage

destruction of

trees):

9 (7.5%)

|

|

|

|

| Table 13.

Plant species favoured

for fuelwood, fire making

and chacoal in the DTC

are |

| Family |

Plant

species |

Rukiga

name |

Life

form |

Use |

| Ericacaeae |

Agauria salicifolia |

ekyigura |

tree |

charcoal |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Bridelia micrantha |

omujimbu |

tree |

fuel |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Sapium ellipticum |

omushasha |

tree |

fuel |

| Fabaceae |

Acacia mearnsii (**) |

obulikoti |

tree |

fuel |

| Fabaceae |

Albizia gummifera |

omushebeya |

tree |

fuel |

| Fabaceae |

Newtonia buchananii |

omutoyo |

tree |

fuel |

| Fabaceae a |

Millettia dur |

omutate |

tree |

fuel |

| Lauraceae |

Ocotea

usambarensis |

omwiha |

tree |

fuel |

| Myrsinaceae |

Maesa lanceolata |

omuhanga |

shrub |

fuel |

| Myrsinaceae |

Maesa

lanceolata |

omuhanga |

shrub |

fuel |

| Myrtaceae |

Eucalyptus spp.

(**) |

uketusi |

tree |

fuel |

| Myrtaceae |

Syzygium guineense |

omungote |

tree |

fuel |

| Proteaceae |

Faurea saligna |

omulengere |

tree |

charcoal |

| Rosaceae |

Hagenia

abyssinica |

omujesi |

tree |

charcoal |

| Rubiaceae |

Galiniera

saxifraga |

omulanyoni |

shrub |

fuel |

| Tiliaceae |

Glyphaea brevis |

omusingati |

tree |

fire tinder |

| Ulmaceae |

Trema

orientalis |

omubengabakwe |

tree |

fue |

Note: Cultivated

exotic species are marked

(**) |

|

FUELWOOD

Although the highest consumption of

wood in the DTC area is for fuelwood (an

estimated 140,000 m³ per year), one DTC

survey (Kanongo, 1990) showed that most

of this is from cultivated trees and only

a small proportion (9 = 7.5%) from the

forest. This is supported by field

observation and data from Kanongo (1990)

that only dry wood is used, as well as

the low prices paid for fuelwood in the

DTC area.

In common with most rural areas in

Africa, fuelwood provides the major

source of household energy for cooking

and heating in the DTC area (Table 12,

page 38). Wood is also used for

distilling waragi, and for baking bricks

and clay pots. Although certain

indigenous species are favoured (Table

13, page 38), crop surplus and cultivated

trees (e.g. black wattle Acacia mearnsii,

73% and Eucalyptus, 58%) are the major

ources of fuelwood. According to one DTC

survey only 7.5% of 120 respondents

obtained fuelwood from indigenous forest.

The impact of dead-wood collection is

low compared to cutting of livewood for

fuel, bean stakes or building materials.

National Parks management should consider

three options in connection with

fuelwood:

- People living around the forest

be allowed to collect dead wood,

including dead trees, possibly on

a twice weekly basis

- Collection of fallen dead wood be

permitted, but not the felling of

dead trees, which provide

important nest sites for barbets

and hornbills, and feeding sites

for woodpeckers.

Attention be focussed on

providing alternative sources of

fuelwood outside the forest,

recognizing that dead-wood use

from multiple-use zones can only

meet a fraction of local needs.

|