Interviews

Professor Sir

Ghillean T. Prance

Former Director of

Research at the New York Botanical Garden

– where he started the Institute of

Economic Botany – and now Director

of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew –

where there is a Centre for Economic

Botany – Professor Sir Ghillean T.

Prance is widely known for his studies of

the ethnobotany, ecology and systematics

of tropical plants. Additional

perspectives on his life and research can

be found in a biography that appeared a

few years ago: Langmead, C. 1995. A

Passion for Plants: from the Rainforest

of Brazil to Kew Gardens. Oxford, Lion

Publishing. Contact: Professor Sir

Ghillean T. Prance, Director, Royal

Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey

TW9 3AB, UK; Tel. +44.181.3325112, Fax

+44.181.9484237, E-mail g.prance@rbgkew.org.uk

Website www.kew.org.uk/GJM

GJM: In the 1980s, when you

were Director of Research at New York

Botanical Gardens, you innovated the

approach of using ecological plots in

ethnobotanical studies. Can you tell me

how you developed this idea?

GTP: Yes, I originally developed

it through conversations with Bob

Carneiro, anthropologist at the American

Museum of Natural History. Bob had some

data from transects he had done with two

groups of Indians in Brazil, including

one in the Xingu Park, and the Yanomami.

He had come to see me, because that is a

group I had worked with also. I thought

these were really useful data, but it was

a pity that we didn’t really know

what the plants were, because he had

recorded just the Indian names. We

decided that we should try to do

something like this more scientifically.

So he and I came up with the idea of

actually laying out some plots amongst

indigenous peoples and doing what we

subsequently termed quantitative

ethnobotany. We furthermore had a

suitable person to do it as a

post-doctoral study, Linda Glenboski. She

had done a study of the Tikuna Indians in

Colombia and was at that time free.

|

We

applied to the US National

Science Foundation for a grant to

do this. We sent it to the

systematic section and they said

“No, this is

anthropology”. We reapplied

to anthropology and they said,

“No, this is systematics,

this is botany”. So it fell

between the cracks and we were

very disappointed because by that

time Linda had to take another

job and we had lost the

opportunity to work with her. We

actually tried three times with

NSF and failed, so we abandoned

the idea. A few years later

– when I had set up the

Institute of Economic Botany at

the New York Botanical Garden

– the president, James

Hester, put me in touch with a

foundation that seemed interested

in ethnobotanical research. |

I phoned Bob Carneiro

and said, “Bob, should we try this

proposal?” We did and they agreed to

fund it. And out of that we were to

appoint Brian Boom as a postdoctoral

researcher. He did the first quantitative

inventory with the Chácobo Indians in

Bolivia and the second one with the

Panare Indians in Venezuela.

GJM: Apart from these initial

studies by Brian Boom, what were some of

the other projects in which you first

used this approach?

GTP: There were two other projects that I

instigated to do this. The first one

involved employing another post-doctoral

researcher at the New York Botanical

Garden, Bill Balée – now at Tulane

University – and getting him to use

the approach with various tribes in the

Southwest Amazon, the Ka’apoor

Indians in Maranhão and the Tembe

Indians, principally. He actually did

quantitative work with three different

tribes. The other project was carried out

by Katy Milton, an anthropologist who is

now at the University of California at

Berkeley. I had nothing directly to do

with the financing, and it wasn’t a

New York Botanical Garden program, but we

discussed the approach and set her off to

do exactly the same thing so we would get

more data from more tribes. So she did

some quantitative ethnobotany in the

upper Amazon. We quickly compiled the

data from quite a large number of tribes.

The same story came out time and time

again, that they really used a large

proportion of the plants in whatever

habitat we were studying. It began to

quantify what conservationists had been

saying all along, that the forest was

important and that the local people

relied on a lot of plants, but it had

never been quantified before.

GJM: The early projects were

all carried out in Latin America and the

approach was most widely used there

particularly in the 1980s. Do you know if

this approach is being used in other

areas such as Africa and Asia?

GTP: I believe it is beginning to be used

in more areas now. I think even more

important is the fact that it was refined

and made mathematically more sound by

work that Oliver Phillips and Al Gentry

did in the Peruvian Amazon. I think that

was actually the next step forward that I

was very pleased about, that had

developed out the approach. But you

probably know more about how it is being

applied in Africa and in Southeast Asia.

GJM: Yes, there are a few

experiences in Africa and Asia, but

ethnobotanical plots are particularly

popular in Latin America. The Smithsonian

Man and the Biosphere plots that have

been set up mostly in Latin America and

the Caribbean always have an

ethnobotanical component, don’t

they?

GTP: That’s right. Here at Kew we

had William Milliken, who I hired. I

continued to develop the idea in Latin

America by obtaining a grant for him to

continue his work with the Waimiri

Atroari Indians. He did quantitative

plots with them, which was particularly

interesting because when he carried out

the study, they were a very recently

contacted group of Indians. So that was

an important application of it because

most of the other groups we worked with

had been in contact with Western

civilization for a much longer time than

the Waimiri Atroari.

GJM: One of the important

aspects of ecological plots is that they

can be compared across regions. That is

what you did in the early work on

quantitative ethnobotany in Latin

America, and the results were published

in Conservation Biology. Do you know if

there has been any attempt since that

article to draw upon additional plots and

to do a broader comparison?

GTP: Not that I know of, and it is

something that I would really like to get

involved in eventually. After starting

the quantitative approach, I became

Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens,

Kew and I don’t do very much field

research. But I have been doing things

like getting people such as William

Milliken to collect more data. I had

another student – I was on his

thesis committee – who has done a

great deal more work in Peru, Miguel

Alexiades [and who just finished his

Ph.D. in the joint program between the

New York Botanical Garden and the City

University of New York]. He has done

quite a lot of very detailed work, which

is excellent, because he spent so long

with the Indians. The other one who I am

supervising is James Cominsky of the

Smithsonian Man and the Biosphere project

that you mentioned. He is doing his

doctorate at London University together

with Barry Goldsmith, an ecologist. We

have lots of data now, and what I think

would really be good is if we could get

plots set up in other places. There is

only one other that I know of, that I

have been involved in Africa, and that

was in Gabon.

GJM: Another one of the

important aspects of ecological plots is

that they allow for long-term monitoring.

This is an important element in

understanding climate change and many

ecological parameters. In ethnobotany, is

long-term monitoring developing as an

important aspect of quantitative studies

in ecological plots?

GTP: It should be, but it hasn’t

been developed nearly enough. There are

two projects in which I think the

research is long-term. One is in Peru,

where the studies that Miguel Alexiades

has carried out include long-term

monitoring in plots, from the original

basic botanical work to the

ethnobotanical work on the plots that

were set up.

|

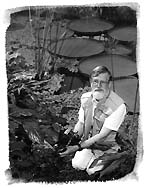

| Professor

Sir Ghillean Prance

examining Xanthosoma leaves

(Araceae). Right: Prance

posing in front of

Victoria amazonica

(Nymphaeaceae) water

lilies growing in the

Royal Botanic Gardens,

Kew. Photos: Andrew

McRobb, © RBG, Kew. |

|

The

other one is the one you have

already cited – the

Smithsonian Man and the Biosphere

work in Bolivia and other

countries. In those two cases,

the ethnobotany has been longer

term. I have been involved in

long-term ecological plot work

quite a lot in the Amazon, but

separated from ethnobotanical

studies. I had a post-doctoral

researcher who worked with me on

this for several years who has

continued it, fortunately, over

the years. He is David Campbell,

who is now at Grinell University.

But I think that long-term

ethnobotanical monitoring is a

very logical and important next

step because it would be very

interesting to do ethnobotanical

studies in plots with different

generations. An experiment that I

wanted to do – but I have

not had the time to do yet –

is to go out to the plots with

three generations from the same

indigenous group and see what

information one gets from the

grandfather, the father and young

people. I think that one would be

documenting some of the

acculturation of local people.

That is a study that someone

needs to do. |

Selected

References

Balée, W. 1994. Footprints

of the Forest. Ka’apor

Ethnobotany – the Historical

Ecology of Plant Utilization by an

Amazonian People. New York,

Columbia University Press.

Boom, B. 1989. Use of plant resources

by the Chacobó. Advances in

Economic Botany 7:78-96.

Campbell, D.G. 1989. Quantitative

inventory of tropical forests. Pages

523-533 in D.G. Campbell and H.D.

Hammond, editors, Floristic

Inventory of Tropical Countries.

New York, The New York Botanical

Garden.

Phillips, O. and A.H. Gentry. 1993a.

The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru.

I. Statistical hypotheses tests with

a new quantitative technique. Economic

Botany 47:15-32.

Phillips, O. and A.H. Gentry. 1993b.

The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru.

I. Additional hypotheses testing in

quantitative ethnobotany. Economic

Botany 47:33-43.

Prance, G.T., W. Balée, B.M. Boom

and R.L. Carneiro. 1987. Quantitative

ethnobotany and the case for

conservation in Amazonia. Conservation

Biology 1:296-310.

BACK

Jan Salick

Jan Salick, Associate

Professor in the Department of

Environmental and Plant Biology, Ohio

University, has criss-crossed the tropics

to carry out ethnobotanical research.

Trained in ecology, she draws on her

background in plant and animal

interactions when studying how people

manage plants. In an interview conducted

at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Jan

discussed her views on how to apply

ecological methods to ethnobotanical

research. We later continued the

interview by E-mail, allowing Jan to

expand on her initial comments. Contact:

Jan Salick, Dept. Environmental and Plant

Biology, Porter Hall, Ohio University,

Athens, Ohio 45701 USA; Tel.

+1.740.5931122/1126, Fax +1.740.5931130,

E-mail salick@ohiou.edu/

GJM

GJM: I know you are familiar

with Professor Prance’s development

of ethnobotanical hectare plots, since

you have worked with him for many years.

As an ecologist, what has been the

importance for ethnobotany of this

quantitative approach?

JS: For a time ethnobotany was a very

subjective and descriptive field with the

publication of long lists of plants used

by various native groups of people around

the world. Since that time,

anthropologists have developed methods

for analyzing ethnobotanical data,

sometimes through linguistic

classification. At the same time, Prance

was a leader in developing methods to

systematically collect, analyze and

compare ethnobotanical plant data from a

botanical point of view. For botanists,

he is extremely influential in moving

ethnobotany from description to

scientific investigation. As a single

major contribution, Prance’s hectare

plot, which standardizes and quantifies

ethnobotanical investigation, has had a

major impact on the development of modern

ethnobotany.

GJM: When we were giving a

course together in Kinabalu Park [Sabah,

Malaysia] in September 1997, you

mentioned that quantitative ethnobotany

can go beyond plots. What do you mean by

this?

JS: When I said that we could expand

ecological ethnobotany beyond plots, I

meant two things. First, there are ways

to use plots that we have not done yet.

There is a lot of ecological data being

generated from one hectare plots or even

bigger plots in many places around the

world. Steve Hubbell at Princeton has

50-hectare plots where he and his

colleagues are looking at production

rates, turnover rates and other

ecological processes and ecosystem

studies.

|

| Jan Slick and

Amuesha shaman discussing

non-timber forest

products in the upper

Peruvian Amazon basin.

Photo: © Jan Salick. |

|

If

we take these ecological data and

combine them with ethnobotanical

data, it gives us the basis for

assessing important variables

like sustainable harvest and

production levels. If we take

quantitative plot data this step

further, we would have all that

much more information to use.

Second, hectare plots are a

subsection within the larger

field of ecological ethnobotany.

Plot methods and related

techniques fall under what is

called plant community ecology,

in which we look at

phytosociology, the association

of plants within a forest. |

But within ecology,

there is a whole range of plant and

animal interactions that go beyond

community ecology all the way from

ecological genetics at the micro level,

up to global changes. I was trained in

plant and animal interactions, and this

approach can be applied equally to people

and plant interactions – it works

smoothly and beautifully.

GJM: You have coined the term

ecological ethnobotany to describe your

approach, and I understand that you are

working on a book on the subject. How do

you define ‘ecological

ethnobotany’ in your work and

writing?

JS: Oof! I’m not one for

definitions. I’m more of a doer;

here’s a recipe. Pick up any

introductory plant ecology textbook and

add people. Ask questions like how do

people affect plant genetics; how do

people affect plant populations, plant

communities, ecosystems, landscapes, and

global change? Use the varied theoretical

framework already provided by ecology and

the well-stocked toolbox of ecological

methods. Discover how the multiple ways

in which people affect plants – that

is ecological ethnobotany.

GJM: In what countries and in

what sort of projects have you been

applying this quantitative approach to

studies of people and plants?

JS: I think it can be applied almost

everywhere. Recently, I have worked

mostly in the Amazon and in Central

America. I started out in Southeast Asia

and have worked a bit in Africa. There is

no limitation to it – it is a

theoretical construct with methodological

and analytical tools, rather than

geographically situated. In the Amazon I

worked with a group of indigenous people

called the Amuesha, doing research on

their influence on an incipient

domesticate crop – Solanum

sessiliflorum, basically a tropical

tomato – of which there are wild and

semi-domesticated varieties. These

intercross and people select and nature

selects in the opposite direction. There

are ecological tools that are well

developed for studying this sort of

interaction. By doing reciprocal

transplants and measuring selective

pressures and gene flow in experimental

regimes, I was able to model the whole

process of human domestication as it

occurs today. This gives much more

detailed information than a purely

theoretical approach where we have to

guess at what has happened in the past.

We can actually measure domestication in

the field.What ecological ethnobotany

allows us to do is set up a hypothesis

and test it. It gives us methods for

analysis. I think that it is very

powerful for testing reality. And the

results are often different from what you

would expect – you often get

surprising results. For the tropical

tomato, I didn’t expect that the

method of reproduction would be under

selective pressure and yet it was. Many

of the characteristics that people are

interested in are maternally inherited.

Had I been making a theoretical model

without experimentation I wouldn’t

have guessed that.

GJM: Your work on Solanum

sessiliflorum is a

good example of what you call the genetic

level of ecological ethnobotany. What are

some examples of the plant population and

community levels of ecological

ethnobotany in which you have been

involved?

JS: In Central America, I have been

working on non-timber forest products. My

studies of their distribution and

abundance within the tropical rainforests

of the Atlantic lowland region were plant

community analyses including the effects

of logging and natural forest

regeneration. The methods are borrowed

directly from plant community ecology and

Prance’s hectare plots – we had

14 comparative hectare plots. These

studies showed clearly that non-timber

forest products can be easily

incorporated with natural forest

management and that natural forest

regeneration is capable of maintaining

tropical diversity under management.Some

species however were adversely affected

by logging and among these was ipecac, a

valuable medicinal plant of the tropical

rainforest. So I set about doing a

population ecology study of ipecac to

determine a sustainable harvest level and

its potential in cultivation. The results

were dramatic in that its production in

the wild is so slow that a sustainable

harvest is nearly impossible. On the

other hand, under shaded cultivation it

flourishes and reproduces ten times

faster. This is encouraging news for

local farmers, but cautionary for

conservationists, since producers will

often cut down the understory of the

tropical rainforest to cultivate beds of

ipecac.These two studies used, first,

plant community ecology and second,

population ecology to address applied

ethnobotany problems – a very

straightforward process.

GJM: There is now an emphasis

in ethnobotany on applying results,

especially in conservation and community

development projects. Are the methods and

results of ecological ethnobotany within

the grasp of communities – can they

apply some of the techniques you use? Or

if they cannot carry out the studies, can

they use results of these studies for

conservation and development in a

practical way?

JS: Yes, absolutely, there are lots of

practical ways in which they can be

applied. In the case of the tropical

tomato that I was talking about, I got as

far as collecting recipes for it and

writing a cookbook! This is an

underexploited tropical crop with which

we could do a tremendous amount for

development. People all over the world,

for example Nigerians, have been asking

me for the seed. We have a long way to go

in developing crops for the tropics and

impoverished countries – this is a

big issue. Much of my work has been done

on very applied questions. In Central

America, the research I mentioned was in

collaboration with foresters working on

natural forest management for sustainable

harvest of wood. My work was focused on

trying to supplement timber management

with non-timber forest products. The

approach is very much community-based:

the knowledge was from the community and

the benefits were for the community. For

me, applied ecology led me into

ethnobotany. We are fortunate to be able

to work directly with people and have our

work directly applied – it is not

just theory.

GJM: Do you think that women

are playing a special role in the

development of ethnobotany?

JS: This one I can get my teeth into!

Yes, of course, but I don’t think a

lot of people appreciate the diversity of

why. For a long time in studies of

hunting and gathering, there was a

distinct emphasis on hunting and

sometimes fishing – men’s work.

Slash-and-burn agriculture is described

– slashing and burning – as

men’s work. Women were often not

interviewed because they were difficult

to approach or it was taboo, but it is

not so for another woman interviewing.

Even when talking to men, the information

I get is radically different than my male

colleagues. How many medicinals do you

find for birth control, abortion,

hemorrhaging or menopause? I find many.

Women are gardeners and curers the world

over and their view of the forest, not

centered on timbers and tall cylindrical

trees, is significantly different than

men’s. I’m sure our theoretical

views may prove to be equally

revolutionary for ethnobotany.

GJM: As a longtime member and

current president of the Society of

Economic Botany [SEB, see PPH 1:10], you

have a good perspective on how

ethnobotany has evolved over recent

years. Do you have many colleagues who

share your ecological approach to the

field?

JS: The recent developments in

ethnobotany are staggering. The field has

taken off! Part of this is due to

farsighted leaders like Professor Prance

and another part is due to a real

grassroots ground swell around the world.

I’ve never seen anything like it. I

went to Peru once to give a mundane

professional talk on medicinal plants and

600 people showed up! I had to change the

talk, improvise a good bit, as well as

give it in Spanish since few in the

audience were the English-speaking

professionals I was expecting. People are

convinced ethnobotany is relevant to

their life today. Plants are important to

people. We need to encourage the interest

in ethnobotany at all levels: popular,

student and professional interest.

Additionally, we need to encourage the

diversity of approaches that are

proliferating: botanical, ecological,

anthropological, geographical, and

particularly the approaches that come

through development and conservation. I

am not the type of person to stand up and

say ecological ethnobotany is the only

way. We are all inspired by the diversity

and creativity of the proliferating

approaches. On the other hand, ecological

ethnobotany has many proponents advancing

a multitude of issues at various levels

of analyses. Ecological ethnobotany is

proving to be a very powerful approach.

Selected

References

Salick, J. 1989.

Ecological basis of Amuesha

agriculture. Advances in Economic

Botany 7:189-212.

Salick, J. and M. Lundberg 1990.

Variation and change in Amuesha

indigenous agricultural systems. Advances

in Economic Botany 8:199-223.

Salick, J. 1992. Crop domestication

and the evolutionary ecology of

cocona (Solanum sessiliflorum

Dunal). Evolutionary Biology

26: 247-285.

Salick, J. 1995a. Non-timber forest

products integrated with natural

forest management. Ecological

Applications 5: 922-954.

Salick, J. 1995b. Toward an

integration of evolutionary ecology

and economic botany: personal

perspectives on plant/people

interactions. Annals of the

Missouri Botanical Garden 82:

68-85.

Salick, J., N. Cellinese, and S.

Knapp, 1997. Indigenous diversity of

cassava: generation, maintenance, use

and loss among the Amuesha, Peruvian

Upper Amazon. Economic Botany

51: 6-19.

BACK

|